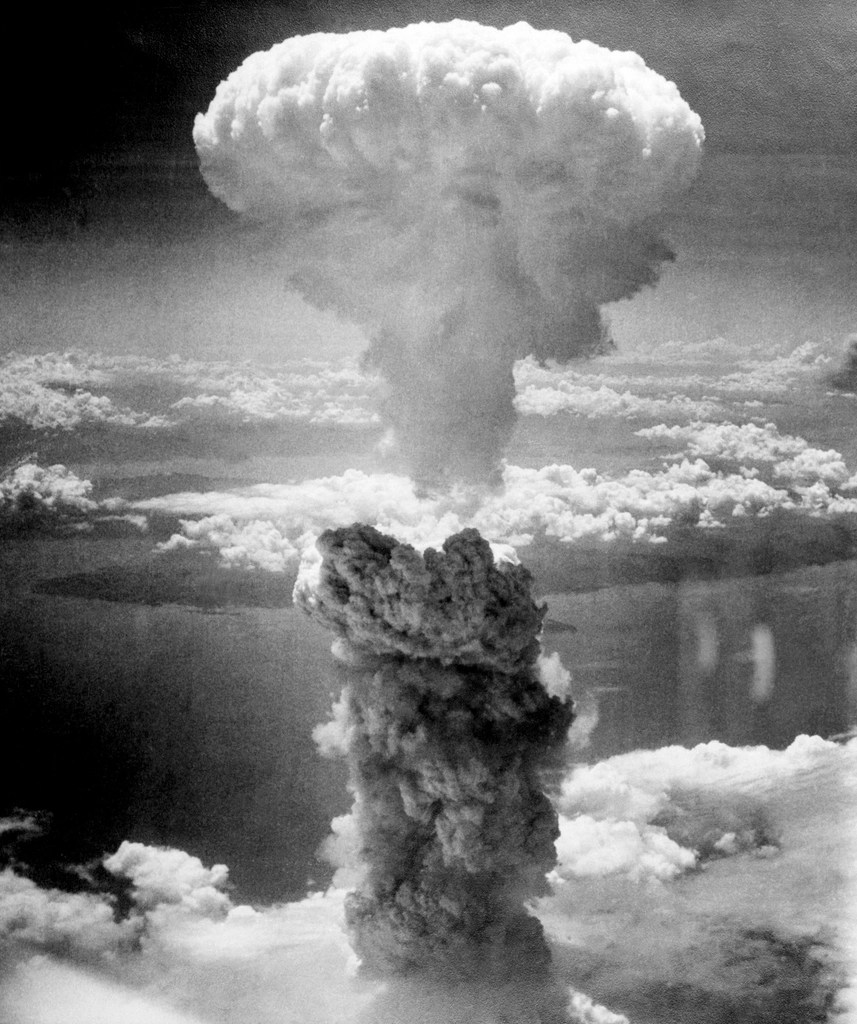

80 years after…

Hiroshima and Nagasaki became the first, and so far the only cities destroyed by atomic bombs.

“I found myself pinned under the rubble in total darkness. I could hear faint cries from my classmates, ‘Mother, help me,’ ‘God, help me.’ Then silence. Out of the darkness, a hand touched my arm and a voice said, ‘Don’t give up. Keep moving toward the light.’” Setsuko Thurlow, 13 years old at the time of Hiroshima. (Thurlow, S., 2017, Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.)

Beyond the staggering loss of over 200,000 lives, these events revealed something unprecedented, humanity had acquired the power to erase itself. It was a test of whether humanity could wield apocalyptic power without destroying itself. We have not yet conclusively passed this test.

The ethical shock of 1945 was not only in the devastation of two cities, but in the recognition that our inherited moral frameworks could not contain the age of total annihilation.

Philosopher Günther Anders called this the Promethean gap, the huge disconnect between what we can do and what we can imagine or take responsibility for. This was not just “more” destruction, it was the potential to end civilization in an afternoon.

Anders, argued that our technological power had outstripped the moral and emotional equipment needed to manage it. Previous weapons had destructive power that could be imagined through direct human experience. However, people could not comprehend the atomic bomb’s destructive capacity. Its annihilation potential was qualitatively beyond understanding.

Anders was deeply disturbed by what he called our “inability to fear adequately.” The danger of nuclear weapons was not only their physical existence, but our psychological distance from their consequences. We cannot fully picture the obliteration of millions. As a result, our emotions lag behind the reality. This makes it easier to tolerate their existence.

For Anders, the shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not just the horror of mass death. It was the realization that humanity had become capable of self-extinction, and yet remained emotionally underprepared to prevent it. The nuclear age, he argued, demanded a radical expansion of moral imagination. This involved an ability to foresee outcomes far beyond our immediate sensory experience. We must also take responsibility for these outcomes.

We remember because forgetting erodes vigilance. We care because the weapons remain, and the same gap between power and wisdom persists. The question is whether, in our time, ethics can catch up.

References

Anders, G. (1956/2003). The Outdatedness of Human Beings (Vol. 1). Munich: C.H. Beck.

Leave a reply to From Trinity to Today: The History and Ethics of the Atomic Bomb – Ethics on Earth© Cancel reply